Non-technical person's guide to becoming an open source software contributor via Github

04 Nov 2014A month ago, I was (lightly, …I think) called out for bailing on speaking about QCTools for the Association of Moving Image Archivists conference. Nevermind the bait-and-switch last-minute-surprise-you’re-speaking scenario I had landed myself in and that I really really did want to see my pals give a talk on BitTorrent and private tracker communities as archives, I did still feel a twinge of guilt for dropping out last minute. Sorry, guys. The BitTorrent panel was pretty baller, though, and Lauren Sorensen did an excellent survey of using git from the command line earlier in the day.

To make up for it, I am here today on this blog to talk about how you, non-technical or kinda-technical or just-scared-of-git person, can dig in and support open source projects like QCTools, even if you don’t speak C++ (which is what I started planning for in the 2-day scramble before leaving New York on a jet plane).

Here it is:

I think a lot of people are intuitively intimidated by using git because it can be hard to understand or because they don’t know how to read code. But not being able to read code is okay because you can still make valuable contributions in English! One of the biggest sore spots for most open source software (and even proprietary software) is a lack of clear, concise documentation. But at least with OSS, if something in the documentation is confusing, instead of going on Twitter or something and being like “wah wah this free thing I downloaded totally sucks,” you can actually go in there and CHANGE it. Or at least make a request to change it.

I’m gonna go through how you might make those changes without having to do anything “techy.”

Uh, so I went to the Flatiron School which is an immersive web development program. This is how I did things on Day 1 as a shortcut to getting what I wanted (which was to deploy a user profile for myself)*. I can’t get away with that stuff now but you totally can. It’s not bad practice or anything (well, maybe the context in which I was doing it was, but that’s neither here nor there). Actually, I did a quick edit like this today because I wanted to fix someone else’s documentation but I didn’t want to bother going through all the other steps to copy and download the repository to my local machine.

* One thousand blessings to Dave Rice for being extremely patient with me when I made my first changes to the QCTools documentation by submitting weird pull requests even though he had given me permission to upload directly because I didn’t know how to push directly to the master branch.

{

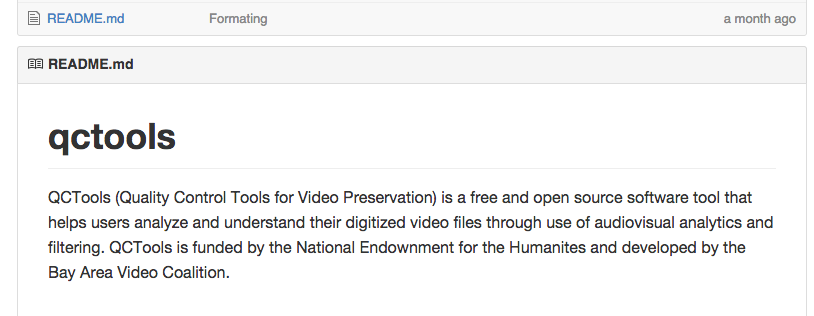

The main block of text on the front of a Github repository is located in the README.md file. (The .md stands for Markdown, a way to format writing on the web easily. (cheatsheet here)) If you click on the link, it’ll take you to a page that only loads the README. On the right side, above the beginning of the document, there is a little pencil button. That pencil allows you to go in and edit the file without having to load the repository on your computer, use the command line, or even use the Github desktop GUI.

That’s right, click on that pencil! You’ll open into an in-browser text editor. It’s pretty much the same as editing a wiki. Which you’ve totally done, right? Just make your changes right in there. At the bottom, fill out a brief, one-line description of the change you made and why you made it and add a longer description if necessary. By the way, you can use emoji in here. Use this cheat sheet.

When you click the “Commit changes” button, you’ll get a notification from Github saying that you can’t directly contribute to the code so it has forked the repository for you and has made your changes on your branch. Does that sound confusing? Forks, branches? It just means that you aren’t allowed to directly change the code and there’s a process in place to make sure that only good code goes in. Everything is copied to your account and you make the changes on YOUR account. If you want the changes to go into the main product, you have to submit a pull request (just follow the steps). It’s a pull request because you are asking the owners of the main github page to “pull in” changes that you made on your copy of their main codebase.

Got a problem? Yo, you’ll solve it! Check out this next step while the DJ revolves it:

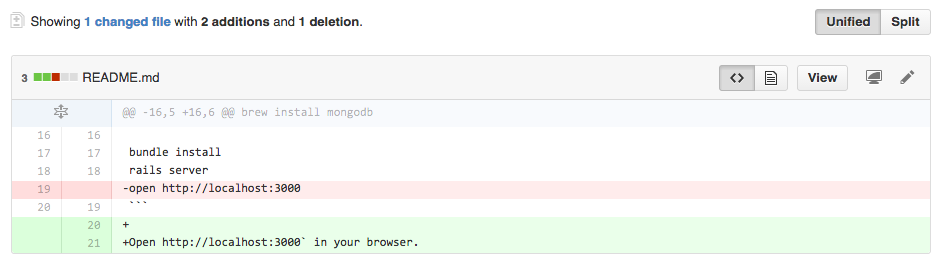

The red is what I took away from the code and the green is what I added in.

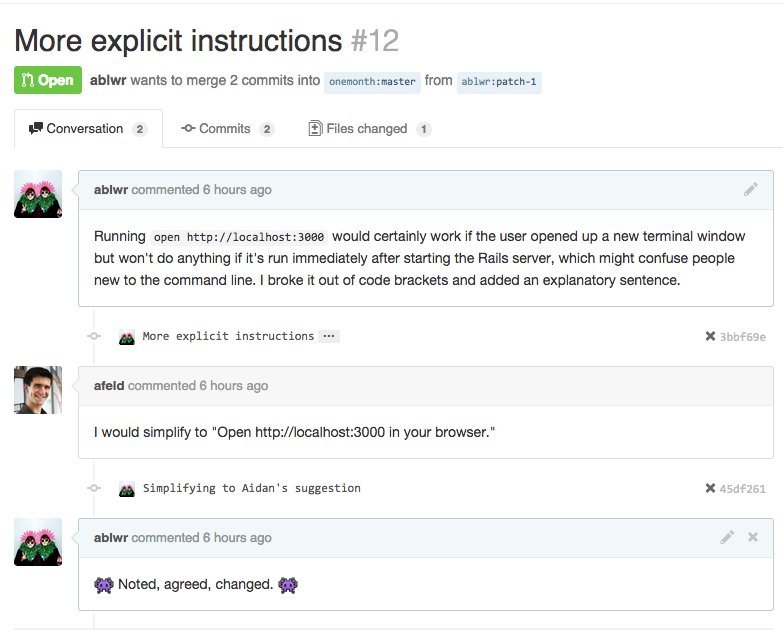

After you submit a pull request, people can comment on it before it can get merged into the master branch. If the code change might cause a problem (or in the case of non-technical edits, if the documentation is wrong), conversations can happen here. This peer-review process helps keep open source projects strong and sturdy. Here is someone coming in to critique my simple edit soon after I opened the pull request on it for being too verbose:

He was right, I could make the line even simpler and not even get into the fact that the code could run in another Terminal window, so I changed my change (the screencap above was taken after that). I even changed my change after this because it still had a lingering backtick in it, as you can see in this screencap. If you change something, you don’t have to re-open a pull request. The pull request takes the latest version of your code on your branch and assumes it is ready to move into the master if the pull request is approved. At this point, all you can do is wait and feel good about your open source contribution.

If you want to add to the QCTools documentation, you can follow the same steps. With QCTools, the documentation is hidden a little deeper into the codebase, but you can find it here in the Source. You have to follow the rules and the code has to validate to proper HTML, but changes are easy and possible.

If you are afraid to make your change, go ahead and try to change anything on any of the repositories I own. I think I even have one called testing. You can’t test out submitting pull requests on your own github folders because you already own them (which was disappointing when I was trying to pull together screen caps for this demo).

If there’s something bigger you want to fix but you don’t know how to do it, you can open an issue. This may or may not be fulfilled and it might take a while to fulfill. Obviously the best way to fix a problem is by doing it yourself. But this is a good way to provide feedback on how something like QCTools works and bring up problems that might be easy to fix by someone else. You can see that QCTools has plenty of open issues at the moment.

The issues page is on the right-hand side of a Github repository. You can access it to see all the current issues or make your own.

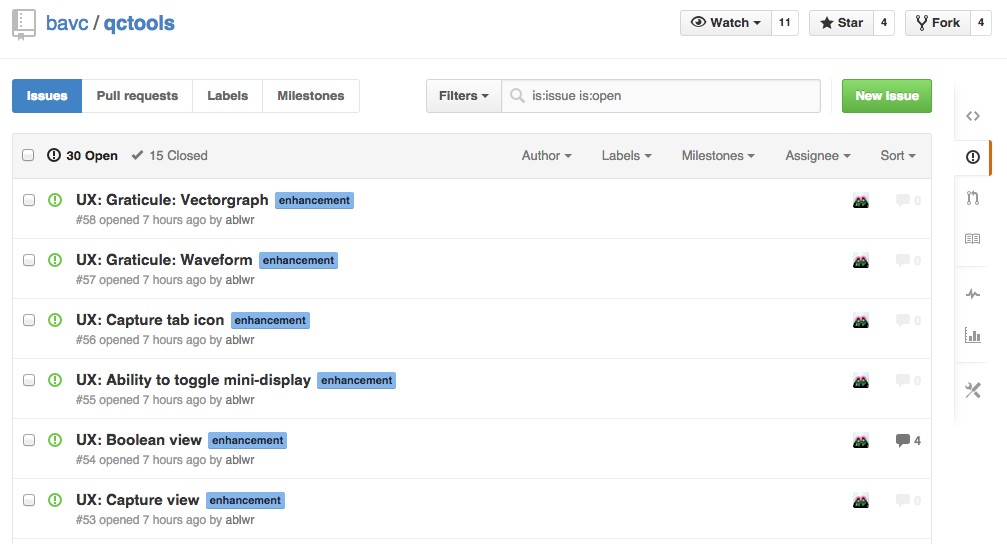

You can see Github has a lot of issues that I added to the repository earlier today. UX needs help, people! To create a new issue, click on the New Issue tab (I didn’t need to explain that to you, did I?)

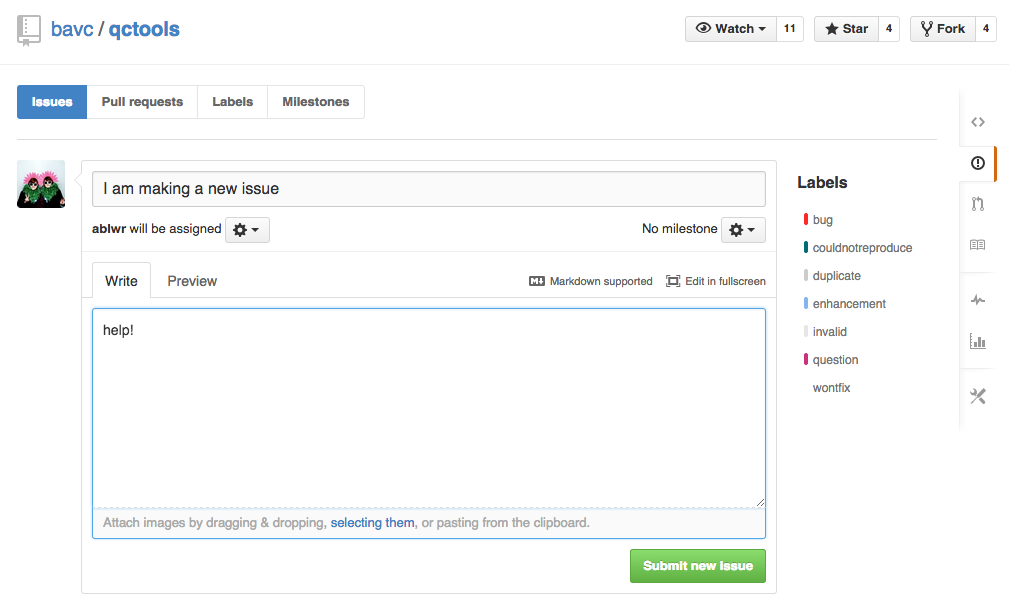

To create a good issue that people will actually pay attention to, try to make the problem specific but concise. If it’s a bug in the program, explain exactly what you were doing to cause the error to occur and make sure to mention if you are able to make the bug repeat, or if it only happened once and not again. If you know someone is in charge of a certain aspect of a project, assign them to it. If you don’t know, though, don’t assign anybody and someone in charge of the project can always direct the issue to the right person or someone else can jump in to fix it. Also, don’t follow my above example and only submit an issue if it’s something important that will help contribute overall to the betterment of the project.

A final note: One thing that guides to Github or Open Source contribution usually fail to mention is that it’s scary. It’s SCARY, dude. It involves being assertive, telling a total stranger that you think you have a better solution to their problem, and envoking feedback from anyone in the world that cares about the project. I don’t have much advice for this other than BE BRAVE, close your eyes, and CLICK that button (or buttons) and don’t worry if someone wants to try to get into a fight with you on the internet. The worst thing that can happen is that you’re wrong, and that’s okay too. And most people are exceptionally nice and willing to work it out with you (like Dave Rice).

The biggest advice I can give is don’t worry about fucking things up. It’s git. It’s a distributed revision control system. It’s entire purpose for existing is to protect against things getting fucked up.

Extra final note: I’m leading a skillshare on git later this month so expect more git-based tutorials or resources to come!