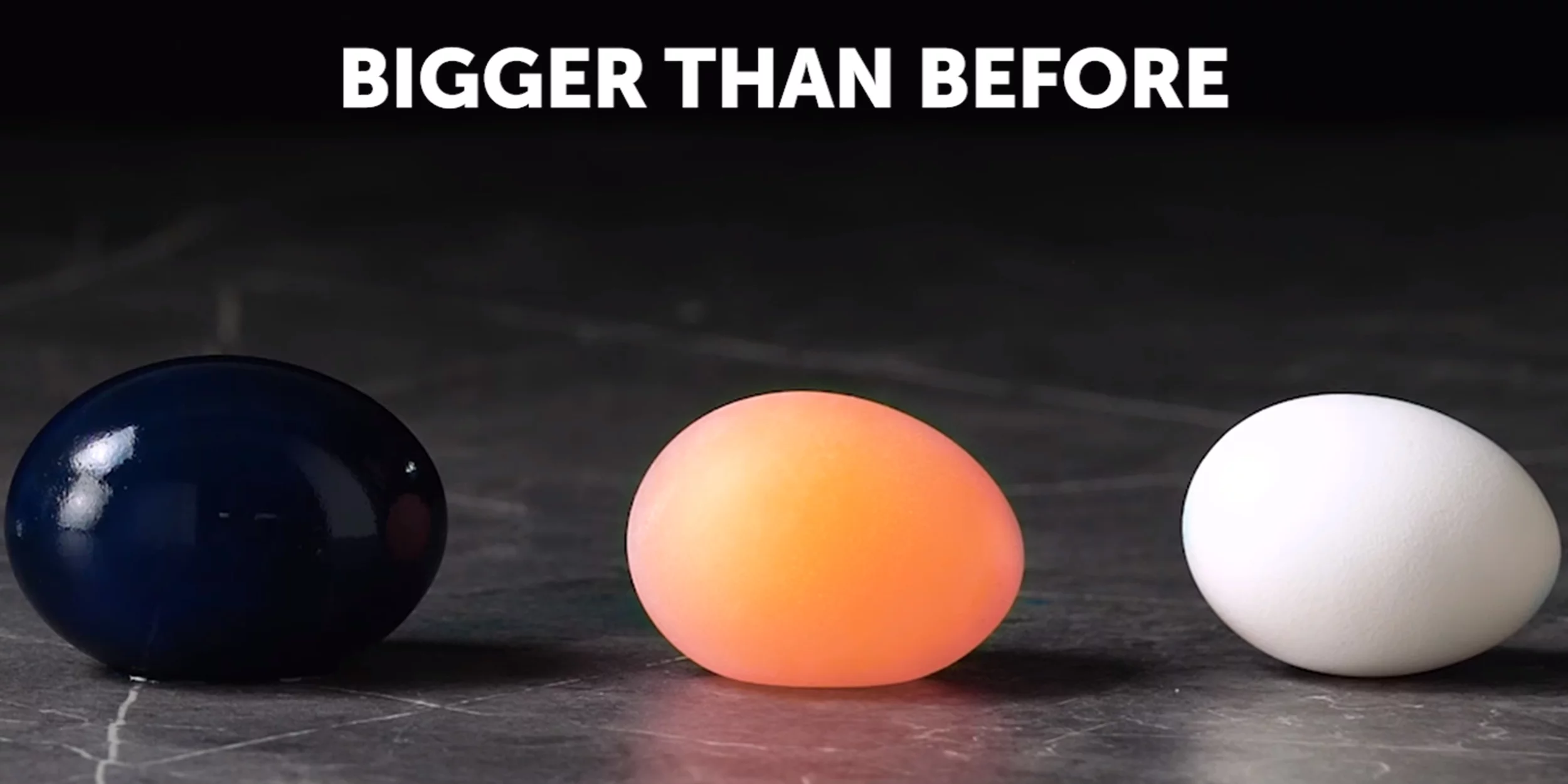

FFV1: Bigger than before

19 Sep 2019

This is one of those blog posts that are a result of me explaining something more than once. I feel like that’s a good guideline for when it’s time to write something up, so that it can be referenced for future question-askers.

Something that keeps coming up in preservation circles is a lament about what

sometimes happens when migrating audiovisual files into the ffv1.mkv format

(Matroska wrapper for

FFV1-encoded video datastream) for

preservation purposes. The complaint is:

“It gets bigger!”

This comes up in short twitter threads (this is the only tweet thread that has ever made me cry) and winding a/v preservation discussions on open source software listservs and also during in-person conversations. Why does it get bigger?

To talk about this problem, I have to back up briefly and talk about the video components themselves and how those work together.

There are many appealing attributes for using Matroska as a video container and FFV1 as an encoding format, including more granular fixity checking, both being open source for integrity and integration in the future and for transparency purposes, reversibility (RAWcooked being an example of this), lossless quality, and more.

Another appealing and much-touted attribute is the

space saving, with an example mentioned here on

Twitter from NYPL’s

Head of Digital Preservation. When thinking through the size of

preservation-grade video assets and storage costs, the savings can be

substantial, especially to those in charge of financing storage of digital

content. So it seems great: saves space, saves money, saves the environment a

tiny bit (okay, maybe a stretch there). So, in theory, when working with

ffv1.mkv, one of the benefits is that these files should get

smaller.

“It gets smaller!”

Some people are getting massive space savings, but others are having files blow up like balloons! What’s the difference?

The difference is all dependent on the source files.

Fundamentally, video files are different. They are often very different.

So: Why do files get bigger when using a basic script to convert files to ffv1.mkv?

I think the most simple answer is maybe “garbage in, garbage out.” Video files can come from a lot of different places: professional digitization, budget digitization, webcams, digital cameras, born-digital video recordings. It’s great when archivists are able to have control over video files that come into the digital world and they can afford to use best practices guidelines to make sure those videos are the highest possible quality. But in this imperfect world, this often isn’t the case. Digitized video coming from low-end digitization hardware are going to be compressing streams of data and encoding them as the digitization happens. This is also true for webcams and digital video cameras (like your phone). These materials are born already-compressed – they come into the world not as a massive, utmost-quality product, as their purpose is speed and quick consumption. Video coming off the web is another example of files that have been compressed for these purposes. This compression is not reversible. The damage has already been done (it’s a different argument in what kind of damage is acceptable, or a quantity vs quality problem). In short, it’s too late for applying “best practices.”

But anyway, in this situation, trying to take a video file that has been intentionally shrunk down and transcoding it into a format that is intended for storage savings on raw data streams is going to result in the files growing. For highly compressed files, this file growth can be massive. It’s a situation of “once you squeeze the toothpaste out of the container, there’s nothing you can do to put the toothpaste back in again.” The data is gone, and making it bigger is not going to increase the quality again. Also since it’s a weird thing to do, it might even make the quality seem worse because it’s trying to stretch out something that has already been shrunk down, like trying to stretch out a wool sweater that has gone through the wash. Anyone who has ever raised a toddler probably has their own story of some very junior person trying to put something back together again and pretending like the adult won’t notice that it’s been completely ruined. I haven’t raised or been around toddlers, but I have, in fact, been a toddler and I know a bad video transcode when I see one.

So for files that have already experienced compression, a migration to

ffv1.mkv is not going to have any positive benefits. You can quit reading now

if you just needed to know that! Otherwise, brace yourself for some opinions

(thinly-veiled as advice). (“My blog, my rules!”)

I have found that people seek out and really want the one perfect solution. In this case, folks are looking for the one perfect format for all of their video materials.

But the world is imperfect, humans are imperfect, and thusly our video files are imperfect, too.

Having worked on the standardization of Matroska and FFV1 (a process that is still ongoing – much praise to the folks getting it over the finish line) and on the MediaConch project and having written papers and given presentations on the merits of this particular kind of video file that I feel is the best choice for preservation of moving image assets, I’ve done my fair share of advocating for its adoption.

Tons of energy have been put into “what is the one perfect format?” because humans love to be right, are tribalistic, and want simple solutions. But I think, in expressing the merits of certain formats over others, it’s the wrong conversation to be having so often. There needs to be more emphasis on, well, the archiving part. What is the context around these files? How did they come to be, and how did they come to be collected?

A time when I absolutely advocate wholeheartedly in favor of an ffv1.mkv file

is when files are moving from their analog media life into the digital world.

This is the time when an archivist (librarian/conservator/whatever) has to think

carefully and critically about the new format, because the original information

has to be radically transformed from physical magnetic media or acetate into

binary data. For a long time, uncompressed video (“v210.mov”) was considered the

best archival standard because it was the highest possible quality, essentially

just a stream of data. The savings difference between this uncompressed

datastream and losslessly compressed encoding can be huge, and the cost savings

over time are significant, too.

But for everything else, it’s important to be critical of both where it came from and from its current technical specifications before applying any kind of treatment, and understanding both of those things. Working with video formats, you should think through the following questions:

- Is this format “at risk”? We all have different threat models in terms of what “at risk” might be, with a phobia of closed-source formats on the high end (my end, tbh) and “Does it play in VLC?” on the reasonable low end.

- Would migration be a burden? If files are already in storage, there should be a very compelling reason to take them out, process them, and swap out the old ones for the new ones. I’d argue some major planning and cost-saving comparing ffv1.mkv to v210.mov could merit this, if you have a lot of video.

- Is this just video, or video as part of a mixed-materials collection? Especially for born-digital materials and with emulation as a viable replay solution, it is likely better to not try to change up any of the materials.

- Already lossy? If the materials you’re working this have already experienced digital loss through video compression, transforming the materials into a high-quality lossless encoding is not going to make the video look better. It might make it worse. It will almost certainly make it bigger.

For some more reading on this, Peter Bubestinger-Steindl has some good advice around this in AV RD’s FAQ Page: “Would you always transfer born digital files into your archive format (FFV1)?” and recommends how to handle specific formats.

Happy transcoding!